What do I read next after To Kill a Mockingbird?

This post discusses several published essays, articles, and readings that students can further study after reading To Kill a Mockingbird.

- A Gathering of Old Men, Ernest Gaines’s 1983 novel. A white Cajun work boss is found shot in a black man’s yard. 19 elderly black men and a young white woman all claim responsibility for the murder in order to thwart the expected lynch mob.

- Song of Solomon (1977) by Nobel Prize-winner Toni Morrison. Milkman Dead searches for his identity. He discovers his own courage, endurance, and capacity for love and joy when he discovers his connection with his ancestors.

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn 1884 by Mark Twain. The popular and sometimes controversial classic follows the satirical adventures and moral development of Huck Finn, a young white boy. Huck accompanies Jim, an escaped slave, down the Mississippi River in a quest for freedom.

- Uncle Tom’s Children (1938), Richard Wright’s collection of stories. He relates the African Americans struggle for survival in a racist world. He explores themes of fear, violence, flight, courage, and freedom.

- Parting the Waters: American in the King Years, 1954–63 by Taylor Branch’s. It won the 1988 National Book Critics Circle Award for nonfiction. Parting the Waters looks at the state of the American civil rights movement between World War II and the 1960s. While focusing on the life of Martin Luther King, Jr., the work also includes profiles of other important leaders and traces key historical events.

Source: Darren Felty’s essay for Novels for Students (1997)

Scout’s encounter with Boo Radley makes Atticus’s lessons about tolerance tangible and personal; Tom Robinson’s trial teaches her about intolerance on a social level. But Lee does not treat this trial solely as a means to develop Scout’s character. Instead, the Tom Robinson story becomes the vehicle for Lee’s overt social criticism in the novel.

We see the town of Maycomb in its worst light. They were willing to execute an innocent man for a crime he did not commit rather than question their belief in black inferiority and their social taboos about interracial relationships. Lee wants to make explicit the consequences of racism and to guide the reader’s judgment of this episode in the novel.

She accomplishes these goals, in part, by employing Tom Robinson’s trial to allude to the famous “Scottsboro Boys” trials of the 1930s. These trials featured 9 black defendants accused of rape by two white women. Despite a lack of evidence and the questionable credibility of the witnesses, the men were sentenced to death by an all-white jury. Unlike Tom Robinson, all of these men escaped death after a long series of new trials in some of which the defendants were still convicted in spite of the evidence. These trials, like Tom Robinson’s, revealed the deep-seated racial divisions of the South and the tenacious efforts to maintain these divisions.

With the “Scottsboro Boys” trials as historical echoes, Lee points to fundamental American ideals of equality and equal protection under the law. As expressed by and portrayed in Atticus, Lee criticizes the people’s failure to meet those ideals. Through Lee’s treatment, the white citizens of Maycomb become hypocrites, blind to the contradictions in their own beliefs. Hence, these people are judged, however benignly, by their own standards, standards which the reader shares.

Many of the lessons Tom Robinson’s story dramatizes escape Scout’s comprehension. Regardless, the reader still recognizes them, as does the older Jean Louise. The town of Maycomb is a sustaining force in Scout’s life; and she views it uncritically as a child and even shares its prejudices. During the trial, she answers Dill’s distress over the prosecuting attorney’s sneering treatment of Robinson, “Well, Dill, after all he’s just a Negro.” She does not experience Dill’s visceral repulsion at the trial’s racist manipulations; instead, she accepts the premise that blacks are treated as inferiors, even to the point of their utter humiliation. But this attitude stems mostly from her immaturity and inability to comprehend the ramifications of racism.

Ultimately, Tom Robinson’s trial and death initiate Scout’s early questioning of racist precepts and behavior. She sees the effects of racism on her teachers and neighbors, and even feels the sting of it herself. Because of Atticus’s involvement with Tom Robinson, for the first time the children must face the social rejection caused by racial bias. They become victims of exclusion and insult, which they would never have expected.

Lee poses a limitation on her social critique in the novel. She it almost completely through the Finch family rather than through Tom Robinson and his family. This focus makes sense given the point of view of the novel; still, it keeps the Robinson family at a distance from the reader. Calpurnia acts as a partial bridge to the black community, as does the children’s sitting with the black townspeople at the trial. But we still must discern the tragedy of Robinson’s unjust conviction and murder predominantly through the reactions of white, not black, characters; this is a fact many might consider a flaw in the novel.

Like the children, the reader must rely on Atticus’s responses and moral rectitude to steer through the moral complications of Robinson’s story. His is a tolerant approach, warning the reader against overharsh judgment. He teaches the children that their white neighbors, no matter their attitudes, are still their friends and that Maycomb is their home. Yet he also asserts that the family must maintain its resolve. “The one thing that doesn’t abide by majority rule is a person’s conscience,” he says. We see the results of Atticus’s words and behavior in the older Jean Louise, who becomes a compassionate yet not uncritical member of her community, both local and national.

Finally, through the Finch family’s resolve and sympathy, Lee lyrically communicates the need to cherish and protect those who, like mockingbirds, do no harm. The are especially vulnerable to the violent injustices of our society.

Claudia Durst Johnson’s “The Mockingbird’s Song” (1994)

In the following excerpt, Johnson explores the role of stories, art, and other forms of communication in Lee’s novel.

The subject of To Kill a Mockingbird is also song, that is, expression: reading and literacy; both overt and covert attempts at articulation; and communicative art forms, including the novel itself. The particulars of setting in the novel are children’s books, grade school texts, many different local newspapers and national news magazines, law books, a hymnal, and the reading aloud of Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe. Much of the novel’s action is actually reading, for as the locals and the children believe, that is Atticus Finch’s only activity. These expressions are not only attempts to have the self broadcast and realized; more significantly, they are attempts to establish connections beyond or through boundaries.

Contrary to the notion that language and art are cold, in TKM, language and art are usually borne of love and linked to expressions of charity and affection. (For example, the Dracula theme frequently expresses the cold tendency of artists to sacrifice everything, even their own humanity, for their art).

The Gothic degeneracy of TKM derives from love’s opposite; imprisonment and insularity, producing, in the extreme, incest and insanity, a gazing in or a gazing back. Its opposite is the social self, which is civilized in its high and positive sense; it reaches out in the love that overcomes ego in language and art. Language and other modes of communication are usually not only civilizing in a very positive way. They are avenues of benevolence, and even charity and love.

In the novel, we remember Scout reading in Atticus’s lap. Atticus reads as he keeps vigil beside Jem’s bed. Atticus was armed only with a book as he plans to protect Tom Robinson from a lynch mob. The society that imprisons Tom Robinson is the same one that imprisons Scout in the “Dewey Decimal System”. Jem’s garbled version of the pedagogical theories of the University of Chicago’s father of progressive education, John Dewey, which are being faddishly inflicted on the children of Maycomb. The practical result of Dewey’s system on Scout is to diminish or hinder her reading and writing; and along with it, her individuality.

Each child is herded into a general category that determines whether he or she is “ready” to read or print or write. (“We don’t write in the first grade, we print”). The life of the mind and reading in particular is replaced in this progressive educational world with Group Dynamics, Good Citizenship, Units, Projects, and all manner of clichés. As Scout says, “I could not help receiving the impression that I was being cheated out of something. Out of what I knew not, yet I did not believe that twelve years of unrelieved boredom was exactly what the state had in mind for me.”

As it is in a black man’s account of slavery (Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass), reading and writing are major themes in TKM. Reading is first introduced with Dill’s announcement that he can read; and Jem’s counterboast that his sister, Scout, has been reading for years:

“I’m Charles Baker Harris,” he said. “I can read.”

“So what?” I said.

“I just thought you’d like to know I can read. You got anything needs readin’ I can do it.…”

The theme continues with Scout’s difficulty with her first grade teacher, who resents that Scout is already able to read when she enters school. The heartfelt importance of reading to the child is considered as she contemplates its being denied to her. One notes in the following passage that reading is inextricably connected with her father and with the civilizing, everyday business of this world; that it is somehow as natural as breathing; and that she has learned that it is a crime in the view of her teacher, possibly because reading and writing (the latter taught to her by Calpurnia) are means of empowerment that place her beyond the control of her teacher.

I mumbled that I was sorry and retired meditating upon my crime. I never deliberately learned to read, but somehow I had been wallowing illicitly in the daily papers. In the long hours of church—was it then I learned? I could not remember not being able to read hymns. Now that I was compelled to think about it, reading was something that just came to me; as learning to fasten the seat of my union suit without looking around, or achieving two bows from a snarl of shoelaces.

I could not remember when the lines above Atticus’s moving finger separated into words. But I had stared at them all the evenings in my memory. I listened to the news of the day, Bills To Be Enacted into Laws, the diaries of Lorenzo Dow, anything Atticus happened to be reading when I crawled into his lap every night. Until I feared I would lose it, I never loved to read. One does not love breathing.

Atticus’s civilizing power comes from his reading. This was a power he has taken on in place of the power of the gun. It is his sole pastime. The narrator reports, Atticus did not do the things our schoolmates’ fathers did. He never went hunting. He did not play poker or fish or drink or smoke. Atticus sat in the living room and read. He is reading under the light outside the jail, with only a book and without a gun for protection, when the mob from Old Sarum arrives to harm his client, Tom Robinson. The novel closes with Atticus reading a book in Jem’s room as he watches over his son.

Members of The Idler’s Club, the old men whose chief activity is attending court sessions together, know him as a lawyer whose skill arises from his being “‘a deep reader, a mighty deep reader”. They disparage his reluctance to depart from the civilizing force of the law by saying, “‘He reads all right, that’s all he does.” The love of reading is also true of Jem. “No tutorial system devised by man could have stopped him from getting at books.”

The theme of reading and writing as emblems for civilization are shown further in Jem’s and Scout’s discussion of what determines a “good” or “quality” or “old” family. Scout recognizes the importance of literacy. “I think its how long your family’s been readin’ and writin’. Scout, I’ve studied this real hard and that’s the only reason I can think of. Somewhere along when the Finches were in Egypt, one of ’em must have learned a hieroglyphic or two, and he taught his boy.” To this Scout replies, “Well, I’m glad he could, or who’da taught Atticus and them; and if Atticus couldn’t read, you and me’d be in a fix.”

By contrast, the more powerless Old Sarum residents and black citizens of Maycomb County are rarely literate; they are generally able only to sign their names. Calpurnia is one of the few black people in the area who can read. She shocks the children with the information that only four members of her church can read. One, whom she has taught to read, “lines” the hymns from the hymnbook for all the others to follow. And finally, in contemplating the meaning of “Old Families,” Scout realizes that literacy has little to do with intelligence. What she doesn’t realize is that it has a great deal to do with power of an intellectual sort.

While reading threads the narrative as surely as the subject of the law does, its meaning is less consistent, more elusive. Despite Scout’s reservation about Jem’s speculation that reading is connected to “Old Families,” it is apparent that, in that it is connected to Atticus; reading denotes a pinnacle of civilized progress. The most civilized, the most humane, the wisest character is the one who reads obsessively.

The continuing powerlessness of the black and poor white people of Maycomb County is incidental to their inability to read, and their children, in contrast to Scout, are taken out of school. Thus, they are denied their only access to power. A related idea is the control that Mrs. Dubose has over narcotics through forcing Jem to read to her.

On the other hand, Zeebo, who leads the singing in the black church, is an example of one who imbues his reading with spirit. He offers it as a gift to his people. Like Calpurnia, he has learned to read from Blackstone’s Commentaries. He uses the language he has been given from the cold letter of the law and imbues it with the warmth and life of the spirit. He alone is able to lead his church congregation in singing hymns like “On Jordan’s Stormy Banks”.

For the three children, reading is a way of sharpening the imagination and gaining knowledge of the Other. The children obsessively make attempts to communicate verbally with Arthur Radley. First, they leave a message for him in the tree, and then, in a blundering fashion, by sticking a note to his window.

Like other dispossessed people in the novel, Boo is doomed to communicate without language. However, we suspect him to be literate, for he gives the children a spelling bee medal. He is also rumored to have stabbed his father in the leg while clipping articles from the newspaper. This begs the question of whether his assault on his father is provoked while he is reading the newspaper. Did it remind him of his forced prohibition from establishing an intercourse with the world?

So Boo attempts to reach out to the world through other means, and he is thwarted again. A real tragedy of Jem’s boyhood, and most likely of Boo’s life, is the severing of their channel of communication, the hole in the oak tree, which Boo’s older brother cements up.

The presents that he leaves in the tree appear to be Boo’s last attempt to reach outside his prison. And each present, which is a means of communication, has significance. The chewing gum seems to be a way of proving that he isn’t poisonous. The penny, an ancient medium of exchange, is something from the past. The spelling medal is also connected with literacy and communication. The carvings are works of art, communication, and love. The aborted mail profoundly affects Jem, who has played the part of Boo in the childhood dramas with conviction.

Right after Jem’s discovery of the cemented hole in the tree, Scout observes that “when we went in the house I saw he had been crying”. For in shutting off Boo’s avenue of expression, Mr. Radley, his brother, has thwarted Jem’s as well. More importantly, he committed what would be a mortal sin in this novel—he has attempted to silence love.

Art forms other than literary ones occur in the novel, sometimes inadvertently communicating messages that the children don’t intend. There is the Radley drama, performed for their own edification, which the neighbors and Atticus finally see. And there is the snow sculpture of Mr. Avery, which the neighbors also recognize. perhaps because these are self-serving art works. They were created without a sense of audience. As if art’s communicative essence could be ignored, the effects of the play and the snow sculpture are not entirely charitable. On the other hand, Boo’s art—the soap sculptures—are lovingly executed as a means of extending himself to the children.

Then there is the story the narrator tells. Art is united with love, somehow making up for the novel’s missed and indecipherable messages, like those so frequently found in the Gothic. The novel is a love story about Jem and Atticus; and to Dill, the unloved child, and Boo Radley, whose love was silenced.

The reader of the Gothic, according to William Patrick Day [in In the Circles of Fear and Desire] is “essentially voyeuristic”. He further states, “Just as when we daydream and construct idle fantasies for ourselves, the encounter with the Gothic [as readers] is a moment in which the self defines its internal existence through the act of observing its fantasies.”

Not only are characters in the Gothic enthralled, but the reader of the Gothic is as well. In the case of TKM, readers learn of the enthrallments of Jem, Dill, and Scout. But the reader of their story is also enthralled, not by the horror of racial mixing or the Dracularian Boo, but by the reminders of a lost innocence, of a time past, as unreal, in its way, as Transylvania.

We, as readers, encounter the ghosts of ourselves, the children we once were, the simplicity of our lives in an earlier world. While the children’s voyeurism is Gothic, our own as readers is romantic. In either case, the encounter is with the unreal. The children’s encounter is in that underworld beneath reality, and ours is in a transcendent world above reality, which nostalgia and memory have altered. It is a world where children play in tree houses and swings and sip lemonade on hot summer days, and in the evenings, sit in their fathers’ laps to read.

Reality and illusion about the past is blurred. Within the novel’s Gothicism and Romanticism, we as readers are enthralled with the past; and, like the responses elicited by the Gothic, we react with pain and pleasure to an involvement with our past world and our past selves.

Jill May’s “In Defense of To Kill a Mockingbird” (1993)

In the following excerpt, May looks at the history of censorship attempts on To Kill a Mockingbird. These attempts came in two onslaughts—the first from conservatives, the second from liberals.

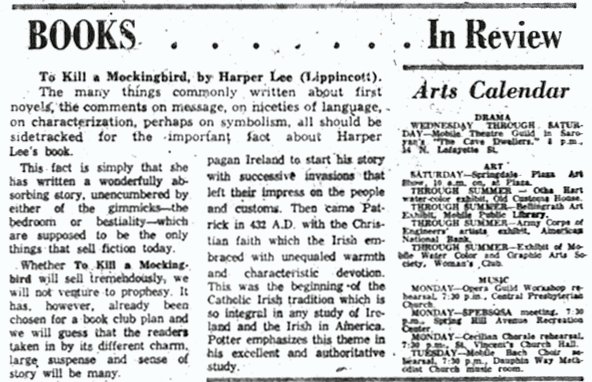

The critical career of To Kill a Mockingbird is a late-twentieth-century case study of censorship. When Harper Lee’s novel about a small southern town and its prejudices was published in 1960, the book received favorable reviews in professional journals and the popular press. Typical of that opinion, Booklist’s reviewer called the book “melodramatic” and noted “traces of sermonizing”. But the book was recommended for library purchase, commending its “rare blend of wit and compassion.” Reviewers did not suggest that the book was young adult literature, or that it belonged in adolescent collections; perhaps that is why no one mentioned the book’s language or violence.

In any event, reviewers seemed inclined to agree that To Kill a Mockingbird was a worthwhile interpretation of the South’s existing social structures during the 1930s. In 1961 the book won the Pulitzer Prize Award, the Alabama Library Association Book Award, and the Brotherhood Award of the National Conference of Christians and Jews. It seemed that Harper Lee’s blend of family history, local custom, and restrained sermonizing was important reading.

And with a young girl between the ages of six and nine as the main character, To Kill a Mockingbird moved rapidly into junior and senior high school libraries and curriculum. The book was not destined to be studied by college students. Southern literature’s critics rarely mentioned it; few university professors found it noteworthy enough to “teach” as an exemplary southern novel.

By the mid-sixties To Kill a Mockingbird had a solid place in junior and senior high American literature studies. Once discovered by southern parents, the book’s solid place became shaky indeed. Sporadic lawsuits arose. In most cases the complaint against the book was by conservatives who disliked the portrayal of whites.

Typically, the Hanover County School Board in Virginia first ruled the book “immoral”. They later withdrew their criticism and declared that the ruckus “was all a mistake” (Newsletter [on Intellectual Freedom] 1966). By 1968 the National Education Association listed the book among those which drew the most criticism from private groups. Ironically it was rated directly behind Little Black Sambo (Newsletter 1968). And then the seventies arrived.

Things had changed in the South during the sixties. Two national leaders who had supported integration and had espoused the ideals of racial equality were assassinated in southern regions. When John F. Kennedy was killed in Texas on November 22, 1963, many southerners were shocked. Populist attitudes of racism were declining, and in the aftermath of the tragedy southern politics began to change. Lyndon Johnson gained the presidency; blacks began to seek and win political offices.

Black leader Martin Luther King had stressed the importance of racial equality; he was always using Mahatma Gandhi’s strategy of nonviolent action and civil disobedience. A brilliant orator, King grew up in the South; the leader of the [Southern Christian Leadership Conference], he lived in Atlanta, Georgia. In 1968, while working on a garbage strike in Memphis, King was killed. The death of this 1965 Nobel Peace Prize winner was further embarrassment for white southerners.

Whites began to look at public values anew, and gradually southern blacks found experiences in the South more tolerable. In 1971 one Atlanta businessman observed [in Ebony], “The liberation thinking is here. Blacks are more together. With the doors opening wider, this area is the mecca.…” Southern arguments against To Kill a Mockingbird subsided. The Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom contained no record of southern court cases during the seventies or eighties. The book had sustained itself during the first period of sharp criticism; it had survived regional protests from the area it depicted.

The second onslaught of attack came from new groups of censors.It came during the late seventies and early eighties. Private sectors in the Midwest and suburban East began to demand the book’s removal from school libraries. Groups, such as the Eden Valley School Committee in Minnesota, claimed that the book was too laden with profanity (Newsletter 1978). In Vernon, New York, Reverend Carl Hadley threatened to establish a private Christian school because public school libraries contained such “filthy, trashy sex novels” as A Separate Peace and To Kill a Mockingbird (Newsletter 1980).

And finally, blacks began to censor the book. In Warren, Indiana, three black parents resigned from the township Human Relations Advisory Council when the Warren County school administration refused to remove the book from Warren junior high school classes. They contended that the book “does psychological damage to the positive integration process and represents institutionalized racism” (Newsletter 1982). Thus, censorship of To Kill a Mockingbird swung from the conservative right to the liberal left. Factions representing racists, religious sects, concerned parents, and minority groups vocally demanded the book’s removal from public schools. With this kind of offense, what makes To Kill a Mockingbird worth defending and keeping?

When Harper Lee first introduces Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird, she is almost six years old. By the end of the book Scout is in the third grade. Throughout the book, events are described by the adult Scout who looks back upon life in the constricted society of a small southern town. Since it is the grown-up Scout’s story, the young Scout Finch becomes a memory more than a reality.

The book is not a vivid recollection of youth gone by so much as a recounting of days gone by. Yet, Scout Finch’s presence as the events’ main observer establishes two codes of honor, that of the child and of the adult. The code of adult behavior shows the frailty of adult sympathy for humanity and emphasizes its subsequent effect upon overt societal attitudes.

Throughout the book Scout sees adults accepting society’s rules rather than confronting them. When Scout finds school troublesome, Atticus tells Scout that they will continue reading together at night. He adds, “You’d better not say anything at school about our agreement.” He explains away the Maycomb Ku Klux Klan, saying, “It was a political organization more than anything. Besides, they couldn’t find anybody to scare.”

Atticus discusses the case of a black man’s word against a white man’s with his brother. He says, “The jury couldn’t possibly be expected to take Tom Robinson’s word against the Ewells … Why reasonable people go stark raving mad when anything involving a Negro comes up, is something I don’t pretend to understand.” The author tells us that Atticus knew Scout was listening in on this conversation. He purposely explained that he had been court appointed. He adds, “I’d hoped to get through life without a case of this kind.”

When the jury does see fit to try and condemn Tom Robinson, Jem and Dill see the white southern world for what it is: a world of hypocrisy, a world burdened with old racist attitudes which have nothing to do with humanity. Jem says, “I always thought Maycomb folks were the best folks in the world; least that’s what they seemed like.” Dill decides he will be a new kind of clown. “I’m gonna stand in the middle of the ring and laugh at the folks.… Every one of ’em oughta be ridin’ broomsticks.”

The majority of white adults in Maycomb are content to keep blacks, women and children in their place. Atticus’s only sister comes to live with the family. She constantly tells Scout she must learn how to act, that she has a place in society: womanhood with its stifling position of prim behavior and wagging tongues is the essence of southern decorum. Even Atticus, the liberal minded hero, says that perhaps it’s best to keep women off the juries of Alabama. “I doubt if we’d ever get a complete case tried—the ladies’d be interrupting to ask questions.”

By the end of the book Scout has accepted the rules of southern society. The once hated aunt who insisted upon Scout’s transformation into a proper young lady becomes an idol for her ability to maintain proper deportment during a crisis. Scout follows suit, reasoning “if Aunty could be a lady at a time like this, so could I.”

The courtroom trial is a real example of Southern justice and Southern local color storytelling. Merrill Skaggs has analyzed the local color folklore of southern trials in his book The Folk of Southern Fiction. Skaggs comments that there is a formula for court hearings. He suggests that local color stories show that justice in the courtroom is, in fact, less fair than justice in the streets. He discusses justice in terms of the black defendant, saying, “Implicit in these stories … is an admission that Negroes are not usually granted equal treatment before the law; that a Negro is acquitted only when he has a white champion.”

During the trial in To Kill a Mockingbird Tom Robinson says he ran because he feared southern justice. He ran because he was “scared I’d hafta face up to what I didn’t do.” Dill is one of Lee’s young protagonists. He is angered by the southern court system. The neglected son of an itinerant mother, Dill is a stereotype of southern misfits. Lee doesn’t concentrate upon Dill’s background; she concentrates upon his humanity.

The courtroom scene is more than local humor to him. It is appalling. When he flees the trial, Scout follows. She cannot understand why Dill is upset, but the notorious rich “drunk” with “mixed children” can. He sees Dill and says, “it just makes you sick, doesn’t it?” No one, save Jem and his youthful converts, expects Atticus to win. The black minister who has befriended the children warns, “I ain’t ever seen any jury decide in favor of a colored man over a white man.”

In the end Atticus says, “They’ve done it before, and they did it tonight, and they’ll do it again. And when they do it—seems that only children weep.” And Miss Maudie tells the children, “as I waited I thought, Atticus Finch won’t win. He can’t win, but he’s the only man in these parts who can keep a jury out so long in a case like that.” Then she adds, “We’re making a step. It’s just a baby-step, but it’s a step.”

In his book, Skaggs points out that obtaining justice through the law is not as important as the courtroom play in southern trials. Because the courtroom drama seldom brings real justice, people condone “violence within the community.” Atticus realizes that “justice” is often resolved outside of the court; so he is not surprised when the sheriff and the town leaders arrive at his house one night.

The men warn Atticus that something might happen to Tom Robinson if he is left in the local jail; the sheriff suggests that he can’t be responsible for any violence which might occur. One of the men says, “—don’t see why you touched it [the case] in the first place.… You’ve got everything to lose from this, Atticus. I mean everything.” Because Atticus wants courtroom justice to resolve this conflict, he tries to protect his client.

On the night before the trial, Atticus moves to the front of the jail, armed only with his newspaper. While there, the local lynching society arrives, ready to take justice into its own hands. Scout, Jem, and Dill have been watching in their own dark corner. But the crowd bothers Scout and so she bursts from her hiding spot. As she runs by, Scout smells “stale whiskey and pigpen,” and she realizes that these are not the same men who came to the house earlier.

It is Scout’s innocence, her misinterpretation of the seriousness of the scene, her ability to recognize one of the farmers and to talk with guileless ease to that man about his own son which saves Tom Robinson from being lynched. The next morning Jem suggests that the men would have killed Atticus if Scout hadn’t come along. Atticus who is more familiar with adult southern violence, says “It might have hurt me a little. But son, you’ll understand folks a little better when you’re older. A mob’s always made up of people, no matter what. Every little mob in every little southern town is always made up of people you know. It doesn’t say much for them does it?”

Lynching is a part of regional lore in the South. In his study of discrimination, Wallace Mendelson pointed out that the frequency of lynchings as settlement for black/white problems is less potent than the terrorizing aspect of hearing about them. In this case, the terrorizing aspect of mob rule had been viewed by the children. Its impact would remain.

After the trial Bob Ewell is subjected to a new kind of Southern justice, a polite justice. Atticus explains, “He thought he’d be a hero, but all he got for his pain was … was, okay, we’ll convict this Negro but get back to your dump.” Ewell spits on Atticus, cuts a hole in the judge’s screen, and harasses Tom’s wife. Atticus ignores his insults and figures, “He’ll settle down when the weather changes.”

Scout and Jem never doubt that Ewell is serious, and they are afraid. Their early childhood experiences with the violence and hypocrisy in southern white society have taught them not to trust Atticus’s reasoning but they resolve to hide their fear from the adults around them. When Ewell does strike for revenge, he strikes at children. The sheriff understands this kind of violence. It is similar to lynching violence. This violence strikes at a minority who cannot strike back, creating terror in lawabiding citizens more potent than courtroom justice. It shows that southern honor has been consistently dealt with outside of the courtroom.

Harper Lee’s book concerns the behavior of Southerners in their claim for “honor,” and Boo Radley’s presence in the story reinforces that claim. When Boo was young and got into trouble, his father claimed the right to protect his family name. He took his son home and kept him at the house. When Boo attacked him, Mr. Radley again asked for family privilege; Boo was returned to his home, this time never to surface on the porch or in the yard during the daylight hours. The children are fascinated with the Boo Radley legend. They act it out, and they work hard to make Boo come out. And always, they wonder what keeps him inside.

After the trial, however, Jem says, “I think I’m beginning to understand something. I think I’m beginning to understand why Boo Radley’s stayed shut up in the house … it’s because he wants to stay inside.”

Throughout the book Boo is talked about and wondered over, but he does not appear in Scout’s existence until the end when he is needed by the children. When no one is near to protect them from death, Boo comes out of hiding. In an act of violence he kills Bob Ewell, and with that act he becomes a part of southern honor. He might have been a hero. Had a jury heard the case, his trial would have entertained the entire region.

The community was unsettled from the rape trial, and this avenged death in the name of southern justice would have set well in Maycomb, Alabama. Boo Radley has been outside of southern honor, however, and he is a shy man. Lee has the sheriff explain the pitfalls of southern justice when he says, “Know what’d happen then? All the ladies in Maycomb includin’ my wife’d be knocking on his door bringing angel food cakes. To my way of thinkin’ … that’s a sin.… If it was any other man it’d be different.” The reader discovers that southern justice through the courts is not a blessing. It is a carnival.

When Harper Lee was five years old the Scottsboro trial began. In one of the most celebrated southern trials, nine blacks were accused of raping two white girls. The first trial took place in Jackson County, Alabama. All nine were convicted. Monroeville, Lee’s hometown, knew about the case. Retrials continued for six years, and with each new trial it became more obvious that southern justice for blacks was different from southern justice for whites. Harper Lee’s father was a lawyer during that time. Her mother’s maiden name was Finch. Harper Lee attended law school, a career possibility suggested to Scout by well-meaning adults in the novel. To Kill a Mockingbird is set in 1935, midpoint for the Scottsboro case.

Scout Finch faces the realities of southern society within the same age span that Harper Lee faced Scottsboro. The timeline is also the same. Although Lee’s father was not the Scottsboro lawyer who handled that trial, he was a southern man of honor related to the famous gentleman soldier, Robert E. Lee. It is likely that Harper Lee’s father was the author’s model for Atticus Finch and that the things Atticus told Scout were the kinds of things Ama Lee told his daughter. The attitudes depicted are ones Harper Lee grew up with, both in terms of family pride and small town prejudices.

The censors’ reactions to To Kill a Mockingbird were reactions to issues of race and justice. Their moves to ban the book derive from their own perspectives of the book’s theme. Their “reader’s response” criticism, usually based on one reading of the book, was personal and political. They needed to ban the book because it told them something about American society that they did not want to hear. That is precisely the problem facing any author of realistic fiction.

Once the story becomes real, it can become grim. An author will use firstperson flashback in story in order to let the reader live in another time, another place. Usually the storyteller is returning for a second view of the scene. The teller has experienced the events before and the story is being retold because the scene has left the storyteller uneasy. As the storyteller recalls the past both the listener and the teller see events in a new light. Both are working through troubled times in search of meaning.

In the case of To Kill a Mockingbird the first-person retelling is not pleasant, but the underlying significance is with the narrative. The youthful personalities who are recalled are hopeful. Scout tells us of a time past when white people would lynch or convict a man because of the color of his skin. She also shows us three children who refuse to believe that the system is right, and she leaves us with the thought that most people will be nice if seen for what they are: humans with frailties. When discussing literary criticism, Theo D’Haen suggested [in Text to Reader] that the good literary work should have a life within the world and be “part of the ongoing activities of that world.”

To Kill a Mockingbird continues to have life within the world; its ongoing activities in the realm of censorship show that it is a book which deals with regional moralism. The children in the story seem very human; they worry about their own identification, they defy parental rules, and they cry over injustices. They mature in Harper Lee’s novel, and they lose their innocence. So does the reader. If the readers are young, they may believe Scout when she says, “nothin’s real scary except in books.” If the readers are older they will have learned that life is as scary, and they will be prepared to meet some of its realities.

Topics for Further Study

- Research the 1930s trials of the Scottsboro Boys and compare how the justice system worked in this case to the trial of Tom Robinson.

- Explore the government programs of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” and explain how some of the characters in To Kill a Mockingbird could have been helped by them.

- Investigate the various groups involved in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s and compare their programs to the community supports found in Lee’s imaginary town of Maycomb.