This post explores in the detail the media adaptation and both the praises and criticisms towards the book, To Kill a Mockingbird, written by Harper Lee.

Media Adaptations

To Kill a Mockingbird was adapted as a film by Horton Foote, starring Gregory Peck and Mary Badham, Universal, 1962; available from MCA/Universal Home Video.

It was also adapted as a full-length stage play by Christopher Sergel. It was later published as Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird: A Fulllength Play, Dramatic Publishing Co., 1970.

Critical Overview

Initial Mixed reviews

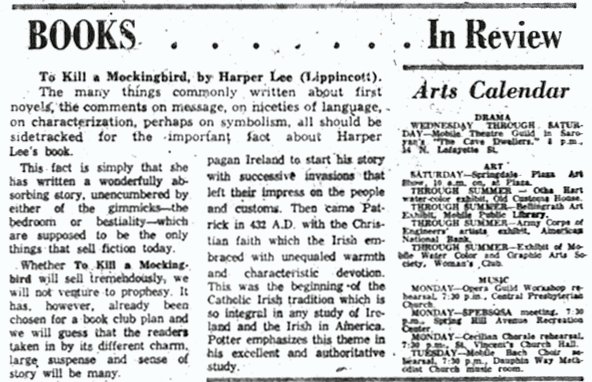

Although To Kill a Mockingbird was a resounding popular success when it first appeared in 1960, initial critical response to Lee’s novel was mixed. Some reviewers faulted the novel’s climax as melodramatic, while others found the narrative point of view unbelievable.

For instance, Atlantic Monthly contributor Phoebe Adams found Scout’s narration “frankly and completely impossible, being told in the first person by a six-year-old girl with the prose style of a well-educated adult”.

Granville Hicks likewise observed in Saturday Review that “Miss Lee’s problem has been to tell the story she wants to tell and yet stay within the consciousness of a child, and she hasn’t consistently solved it.”

In contrast, Nick Aaron Ford asserted in PHYLON that Scout’s narration “gives the most vivid, realistic, and delightful experiences of child’s world ever presented by an American novelist; with the possible exception of Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.”

Other early reviews of the novel focused on Lee’s treatment of racial themes. Several observers remarked that while the plot of To Kill a Mockingbird was not particularly original, it was well executed. New Statesman contributor Keith Waterhouse, for instance, noted that Lee “gives freshness to a stock situation”.

In contrast, Harding LeMay asserted otherwise in the New York Herald Tribune Book Review. The author’s “valiant attempt” to combine Scout’s amusing recollections of her eccentric neighborhood with the serious events surrounding Tom Robinson’s trial “fails to produce a novel of stature, or even of original insight”; although “it does provide an exercise in easy, graceful writing”.

Richard Sullivan, on the other hand, claimed in the Chicago Sunday Tribune that To Kill a Mockingbird is a novel of strong contemporary national significance. It deserves serious consideration. But first of all it is a story so admirably done that it must be called both honorable and engrossing. The Pulitzer Prize committee agreed with this last opinion, awarding the novel its 1961 prize for fiction.

Critical acclaim

Later appraisals of the novel have also supported these favorable assessments, emphasizing the technical excellence of Lee’s narration and characterizations. In a 1975 article, William T. Going called Scout’s point of view “the structural forte” of the novel. He added that it was “misunderstood or misinterpreted” by most early critics. “Maycomb and the South are all seen through the eyes of Jean Louise, who speaks from the mature and witty vantage of an older woman recalling her father as well as her brother and their childhood days.”

Critic Fred Erisman interpreted the novel as presenting a vision for a “New South” that can retain its regional outlook; and yet it treats all its citizens fairly. He praised Atticus Finch as a Southern representation of the ideal man envisioned by 19th century American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson.

“The individual who vibrates to his own iron string, the one man in the town that the community trusts ‘to do right,’ even as they deplore his peculiarities.”

R. A. Dave similarly found the novel a success in its exploration of Southern history and justice. He claimed that in To Kill a Mockingbird “there is a complete cohesion of art and morality. And therein lies the novelist’s success. She is a remarkable storyteller. The reader just glides through the novel abounding in humor and pathos, hopes and fears, love and hatred, humanity and brutality; all affording him a memorable human experience of journeying through sunshine and rain at once.… The tale of heroic struggle lingers in our memory as an unforgettable experience.”

Criticisms

Darren Felty is a visiting instructor at the College of Charleston. In the following essay, he explores how the narrative structure of To Kill a Mockingbird supports a reading of the novel as a protest against prejudice and racism.

Most critics characterize Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird as a novel of initiation and an indictment of racism. The novel’s point of view, in particular, lends credence to these readings. As an older woman, Jean Louise “Scout” Finch, the narrator, reflects on three crucial summers in her childhood. During this time, she, her brother Jem, and their friend Dill encounter two figures who change their views of themselves and their community.

The first of these people, Boo Radley, the Finches’ reclusive neighbor, develops from a “malevolent phantom” who dominates the children’s imaginations, to a misunderstood man who saves Scout’s and Jem’s lives. Tom Robinson, the second and more tragic figure, loses his life because of racial prejudice. This teaches the children about the more malicious characteristics of their society and fellow citizens.

Guided by the ethical example of their father, Atticus, the children attempt to understand the lives of these two men. Gradually, through their exposure to Boo Radley’s life and Tom Robinson’s death, they learn about the grave ramifications of the social and racial prejudice that permeate their environment. Their honest and often confused reactions reflect their development as people. These also help the reader to gauge the moral consequences of the novel’s events.

Boo Radley is a compelling enigma and source of adventure for the children. He also represents Scout’s most personal lesson in judging others based upon surface appearance. In their attempts to see and communicate with Boo, the children enact in miniature their overall objective in the novel: to try to comprehend a world that defies easy, rational explanation.

At first, Boo represents the mysterious, the unfathomable, which to the children is necessarily malevolent. They cannot understand why he would remain shut away, so he must be terrifying and evil. They ascribe nightmarish qualities to him that both scare them and stimulate their imaginations. In Jem’s “reasonable” description of him, Boo is “six-and-a-half feet tall”. He dines on raw squirrels and cats, bears a “long jagged scar” on his face, has “yellow and rotten” teeth and “popped” eyes, and drools. He is, in essence, a monster who has lost all traces of his former humanity. And by never appearing to them, Boo always plays the part the children assign him: the silent, lurking antagonist.

Yet even their imaginations cannot keep the children from recognizing incongruities between their conceptions of Boo and evidence about his real character. The items they discover in the tree knothole, for instance, tell them a different story about Boo than the ones they hear around town. The gifts of the gum, Indian head pennies, spelling contest medal, soap-carving dolls, and broken watch and knife. All reveal Boo’s hesitant, awkward attempts to communicate with them, to tell them about himself.

The reader recognizes Boo’s commitment to the children in these items, as do Jem and Scout after a time. The children, we see, are as fascinating to him as he to them, only for opposite reasons. They cannot see him and must construct a fantasy in order to bring him into their world; he watches them constantly and offers them small pieces of himself so he can become a part of their lives. The fact that Nathan Radley, Boo’s brother, ends this communication by filling the hole with cement underscores the hopeless imprisonment that Boo endures, engendering sympathy both in the reader and the children.

After Boo saves the children’s lives, Scout can direct her sympathy toward a real person, not a spectral presence. Because of this last encounter with Boo, she learns firsthand about sacrifice and mercy, as well as the more general lesson that Atticus has been trying to teach her. “You never understand a person until you consider things from his point of view … until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” Boo left the safe environment of his home to risk his life for hers; and she knows that his essential goodness and vulnerability need protecting.

Hence, he is a like a mockingbird. And to assail him with public notice would be comparable to destroying a defenseless songbird who gives only pleasure to others. As she stands on his porch, she reflects on her former behavior and feels shame.

“Boo was our neighbor. He gave us two soap dolls, a broken watch and chain, a pair of good-luck pennies, and our lives. But neighbors give in return. We never put back into the tree what we took out of it; we had given him nothing, and it made me sad.”

Scout feels remorse over the children’s isolation of Boo because of their fear and the prejudices they had accepted at face value. As a result of her experiences with Boo, she can never be comfortable with such behavior again.